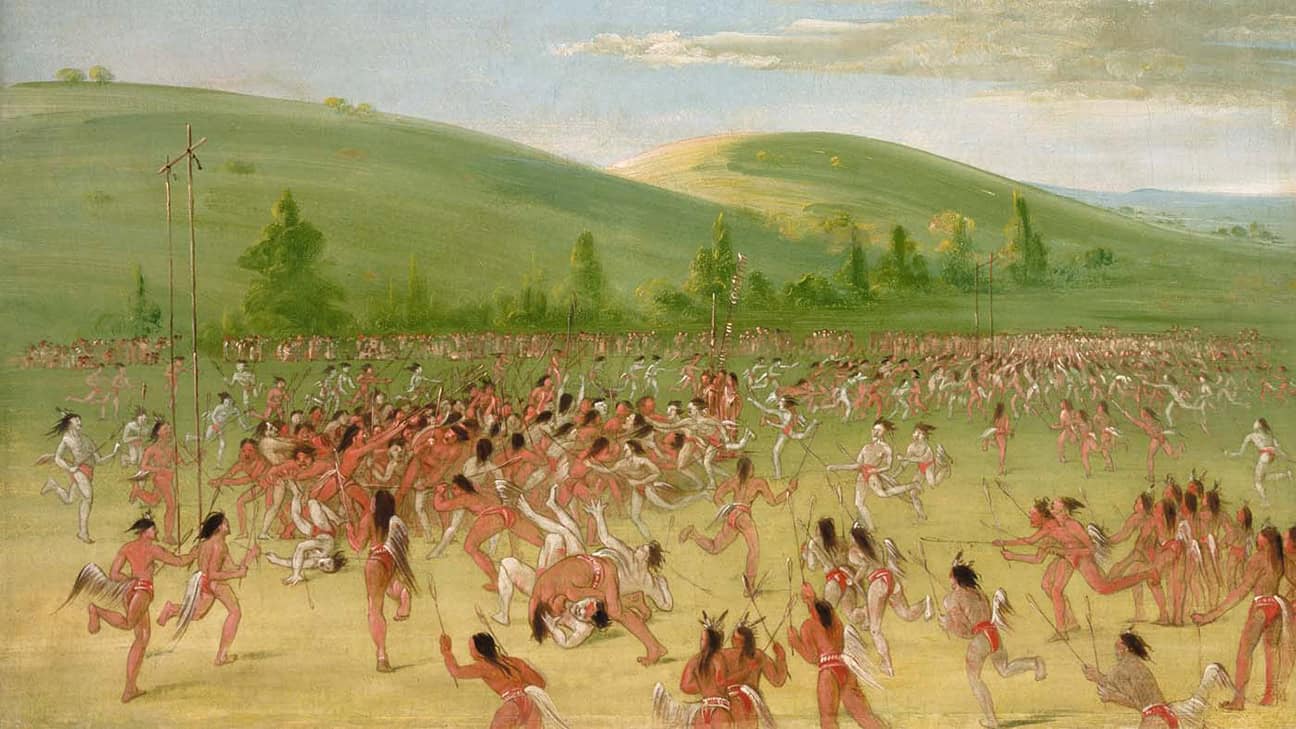

"Ball-play of the Choctaw – ball up" by George Catlin

Culture on the Prairie

Iti FabvssaPublished September 1, 2025Oktak, the prairie landscape, carries deep cultural and ecological significance for many Indigenous communities, especially the Choctaw.

Through cultural memory and ecological intimacy, the prairie reveals a landscape alive with spirit and transformation.

Each hill and stream expresses its own presence. Prairie plants shift weekly in blooming cycles, weaving a vivid tapestry of life. Close observation uncovers countless stories embedded in plants, animals, and insects. The expansive prairie sky, with its ever-changing light and color, enriches this experience.

Many people overlook the prairie ecosystems within the Choctaw homeland, which spans the southern two-thirds of Mississippi and the western third of Alabama.

Before the Trail of Tears, the Blackbelt and Jackson prairies covered over 1.5 million acres of Choctaw lands. Shallow chalk layers in the soil prevented trees from taking root, allowing grasslands to flourish. Nineteenth-century observers described these prairies as seas of wildflowers rising and falling with the wind. Choctaw ancestors expanded and maintained these ecosystems through intentional fire management.

In the southern third of the homeland, the longleaf pine belt functioned as a fire-dependent savanna, where tallgrass prairie species thrived beneath an open canopy of pine trees.

Choctaw oral traditions link the formation of the Blackbelt prairie to the giant animals of the last Ice Age. For centuries, ancestral Choctaw communities thrived in and around these prairies.

During the Battle of Mabilla, Choctaw ancestors and allies resisted the De Soto expedition, demonstrating the cultural and political importance of these landscapes. Spanish chroniclers recorded the Choctaw ancestors’ unwavering commitment to freedom, noting their willingness to fight to the last person rather than submit to colonization.

In response to European-introduced diseases and slaving raids, Choctaw communities reorganized their settlements in Mississippi. Tribal towns emerged in prairie regions, which provided essential resources. For example, women in the early 1700s wore the vlhkuna, a skirt made from dogbane fiber and bison wool – materials sourced directly from the prairie.

The Choctaw language reflects a profound ecological awareness, naming prairie species with precision and poetic insight. Words like hatapofokchi (kestrel), kofi (bobwhite), and tohkil (sensitive brier) reveal how speakers perceive and relate to the prairie’s inhabitants. The term tohkil, for example, refers to the plant’s eyelash-like leaves that close when touched, evoking the image of squinting eyes.

Fossil clam shells often erode from the calcareous soils of the prairies in the Choctaw homeland.

The Choctaw name for these shells, opahaksun, appears to derive from the phrase opa ola ikhanklo – “doesn’t hear the cry of the screech owl.” Given the owl’s cultural association with death, this name invites reflection on how Choctaw people understood and encoded relationships between land, life, and mortality. Such linguistic expressions preserve not only ecological knowledge, but also philosophical and spiritual perspectives embedded in the landscape.

After the Trail of Tears, many Choctaw people relocated to southeastern Oklahoma – a region often mischaracterized as lacking prairie.

Yet early accounts, such as those by naturalist Thomas Nuttall in 1819, document small prairies and buffalo trails throughout what is now the Choctaw Nation Reservation.

Choctaw families established the Nation’s capital, Tushkahoma, in one of these prairie zones. Larger prairie belts stretched along the Red River and extended northward from present-day Durant to McAlester.

Upon arrival, some Choctaw families settled in these areas, building farms and ranches that helped rebuild the Choctaw economy.

In the 1830s, George Catlin painted his famous “Ball-play of the Choctaw – ball up” in a tallgrass prairie near what is today, Poteau, Oklahoma.

Today, tallgrass prairie ecosystems in southeastern Oklahoma face critical endangerment.

Agricultural development, overgrazing, fire suppression, and tree encroachment have nearly erased these landscapes. Only 5-10% of the original tallgrass prairie survives, mostly in the Flint Hills of Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma.This ecological collapse threatens species like the monarch butterfly and bobwhite quail, as well as Choctaw cultural practices rooted in prairie interaction.

The few remaining prairie remnants within the Choctaw Nation hold immeasurable value. These landscapes connect people to Choctaw and Caddo history, offer opportunities for cultural and ecological engagement, and support biodiversity and vital ecosystem functions. Restoration demands intensive labor and long-term commitment, highlighting the urgency of preservation.

The Choctaw Cultural Center grounds in Calera host one of the highest-quality tallgrass prairie remnants in the region.

On October 11, 2025, the Historic Preservation Department, in partnership with the Oklahoma Biological Survey, Okies for Monarchs, and the Cultural Center, will be hosting a BioBlitz on this remnant.

Participants will take guided walks through the prairie with biologists and cultural people to see and learn about prairie species that have deep importance in Choctaw culture as well as Oklahoma ecology. This event is free and open to the public.

To learn more please visit the Events page on the Choctaw Cultural Center website.

Works Cited

- Thompson, I. (2022, July 18). Forged in Heat. nanawaya.com/post/forged-in-heat

- Thompson, I. (2022, January 3). Practical Prairie Rehabilitation – Little Bluestem. Mysite. nanawaya.com/post/practical-prairie-rehabilitation-little-bluestem

- Thompson, I. (2023, February 4). Choctaw heritage on the Prairie. nanawaya.com/post/choctaw-heritage-on-the-prairie