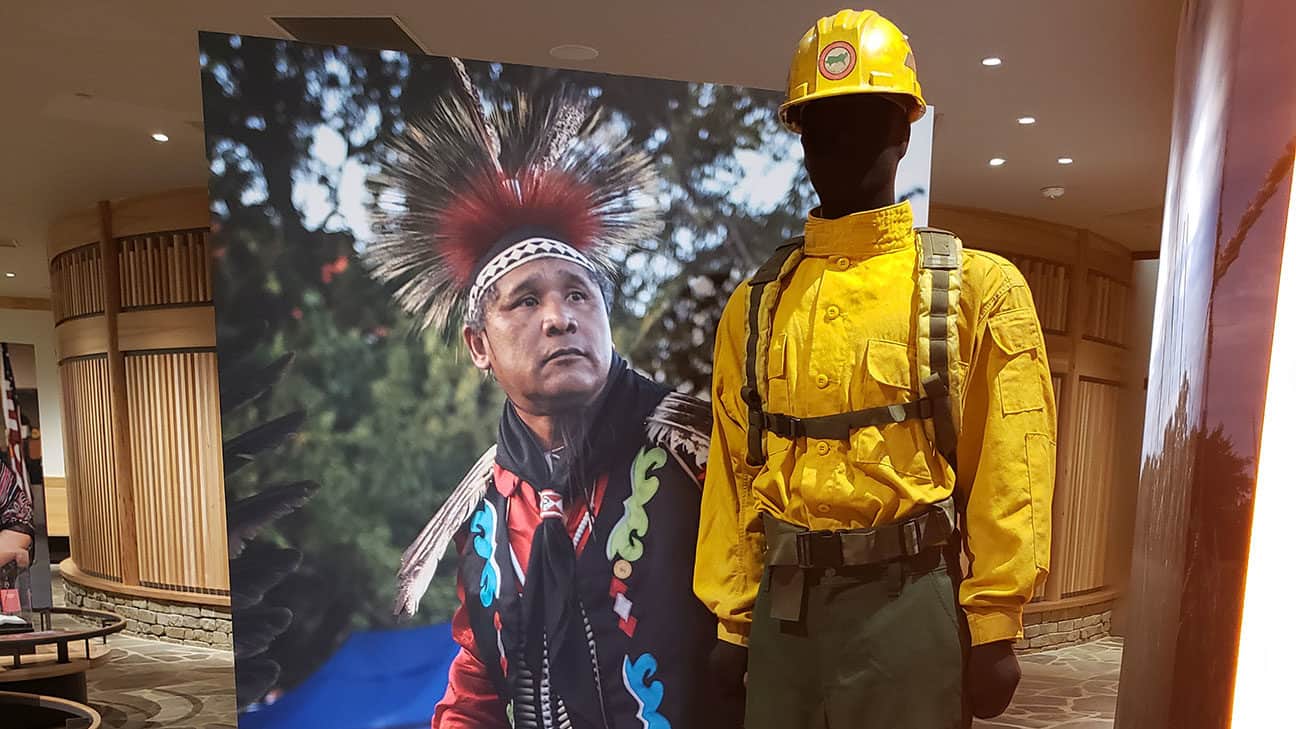

In Honor of our Choctaw Firefighters

Iti FabvssaPublished February 1, 2022This month Iti Fabvssa is taking a brief intermission from “A New Chahta Homeland: A History by the Decade” series to honor our Choctaw firefighters. Since time immemorial, Choctaw people have had a relationship with fire through the land. Like many other Indigenous communities across North America, Choctaw people have used fire for land management to create open, biologically diverse environments that lead to better habitats for animals and edible plants. The decline in traditional fire management combined with climate change has increased the risk for dangerous fires throughout North America. Nevertheless, Choctaws have found new avenues to carry on that relationship.

In response to the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Indian Division was established to create new employment opportunities and recruited Native people as firefighters in the 1930s. These men were trained and deployed to assist at large-scale fires. Federal and State agencies utilized these crews throughout the United States when the need arose. For example, Aaron Baker and other Choctaws from the McCurtain County area worked for the CCC’s Division of Forestry for the State of Oklahoma for 30+ years (Robert Baker, personal communication, 2021). Although this program no longer exists, Choctaws worked in firefighting through other programs.

As part of the Choctaw Nation’s revitalized sovereignty, Choctaw Nation Forestry partnered with the United States Forest Service (USFW) in 1989 to train and deploy Type 2 Fire Crews (Tom Lowry, personal communication, 2020). The Forest Service divides its Fire crews into three types, each crew having 18 to 20 members. Type 1 Crews, also known as Interagency Hotshot Crews, function as a highly trained, skilled and qualified crew. The Type 2 Initial Attack Crew could be divided into several individual squads, each with their own incident commander, to strategically attack fires. Lastly, the Type 2 Crew has one incident commander and works as a single 20-person unit. These crews are responsible for creating fire lines that help stop the spread of fires using a variety of tools and equipment.

During the 1990s, the Choctaw Nation was facing unemployment rates as high as 40%. Many Choctaw men and women did not have opportunities to work due to the lack of infrastructure in Southeastern Oklahoma. The USFW worked with Choctaw Nation Forestry to host one-week trainings at our Capitol Ground in Tvshka Homma. After the training, each Firefighter was given money to purchase a specific type of boot. Most Choctaw firefighters know this boot well. At eight pounds, this boot required a 1″ Vermeer sole with a 2″ heel. This was their first piece of firefighting equipment and without it, they could not go fight fires (Ernest Baker, personal communication, 2020).

Choctaw Nation Forestry would assist with up to four deployments to fight fire per year. When Choctaw Nation Forestry sent out the call, Choctaw fire crew members that were available for duty would make their way to Talihina. Wearing their boots and red t-shirt, they checked out their equipment and loaded the bus. Flying out of Fort Smith, these brave men and women would leave their families and communities for 21 days to protect others in need (Tom Lowry, personal communication, 2020). Choctaw firefighters would commonly work alongside other Native firefighter crews. If Choctaw Nation had extra firefighters, they would be assigned to other Native Crews to meet the 18–20-person crew minimum.

The daily life of a Choctaw Firefighter was rugged. These Choctaws worked 12-to-16-hour days using shovels, rakes, chain saws and the famous Pulaski. The Pulaski is a specialized tool used by firefighters that combines both an axe and adze that would assist them in building and clearing fire lines. On average, Choctaws crews were known to cover 10 miles worth of fire line a day. At camp, they had access to all different types of foods and fruits and a commissary where they could buy items they may need. Every few days, they were able to call their families for short five minute conversations (Ernest Baker, personal communication, 2020). They slept side by side in two large canvas tents at night. Upon returning home, they would wear their blue t-shirts. After they checked in their equipment at the Choctaw Forestry Office in Talihina, they handed their check and returned home to their families.

According to Tom Lowery, Choctaw Nation’s Type 2 Crew became known as the Choctaw BMF or Buffalo Mountain Firefighters (Tom Lowry, personal communication, 2020). For many on the crew, this was the first job that was ever offered to these men and women. They were given purpose, direction, and a cause to fight for. The Choctaw BMF were quite efficient – they kept up and sometimes surpassed the Type 1 Crews. Through the years, the Choctaw BMF earned a reputation as being one of the best Type 2 crews that could be fielded. At the Annual Idaho Fire Chiefs Association Conference, all the wall-mounted displays honored each Type 1 Crew and one Type 2 Crew, the Choctaw Buffalo Mountain Firefighters.

Choctaw fire crews were temporary work. As the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma began to expand and create more diverse jobs within Southeastern Oklahoma, the allure of full-time work with benefits appealed to those that needed to support families. Less people took the firefighting training. By 2003 the Choctaw Nation was no longer able to field 20-person crews but continued to work with other Tribes by combining their crews together. In 2021 the USFS terminated its firefighting contract with the Choctaw Nation, partly because there were only a handful of firefighters available through the tribe but also because the future of firefighting is changing.

The history of our Choctaw Firefighters is still recent. If you have family members who served as Choctaw firefighters, we would like to encourage you to reach out to them and record their stories. If you need help getting started, a “Guide to using time at home to record oral family histories” is available online.

If you would like to share your stories with the Choctaw Nation Historic Preservation Department, we can store them digitally for future access for your family members.